A blog about about painting, design and other aspects of aesthetics along with a dash of non-art topics. The point-of-view is that modernism in art is an idea that has, after a century or more, been thoroughly tested and found wanting. Not to say that it should be abolished -- just put in its proper, diminished place.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Irwin Caplan Playing Shakespeare

Irwin Caplan (1919-2007) was a well-known magazine cartoonist during the final glory years of the "slick" general-interest magazines. As his Wikipedia entry indicates, Caplan practiced a good deal more art and design than those cartoons. But it was the cartoons that most people knew about.

In the pre-Internet age it wasn't so easy to locate information about people, so that's why I was surprised regarding all his non-cartooning accomplishments when reading the link above. You see, I encountered him Way Back When.

I was majoring in commercial art at the University of Washington and one of the classes in that field was Fashion Illustration. And our instructor was ... Irwin Caplan, of all people: the famous cartoonist.

A slight problem I had with that was a lack of credibility: What did he know about fashion illustration? Perhaps sensing this, one day he brought in a newspaper clipping of a small advertisement for a blouse where the illustration was a wash drawing by Himself. He told us that even though the illustration was small, it was his and it got published, so he was proud of that.

That helped some, but we were most pleased when he brought in his buddy (and well-known local fashion and general-purpose illustrator) Ted Rand and his lovely wife for a demonstration. Oh, how jaded and snobbish we were in our student days!

Monday, March 28, 2011

Two Steps Removed from Sorolla

While on my gallery crawl along Palm Desert's El Paseo I came across some paintings that seemed very like the work of Joaquin Sorolla. But they weren't, of course.

Information on the plaque indicated that the artist was Giner Bueno (1935 - ). And a little Internet digging revealed (click on the link) that he, like Sorolla, was born in the Valencia area. This link notes that his father, Luis Giner Vallas, was a protege of Sorolla.

Below are some examples of Giner Bueno's work.

Al Mediodia

Maternidad

La Pesca

El Regreso

Scenes similar to Sorolla's along with minor theme variation.

En Chelva

Giner didn't spend all his time on the shore.

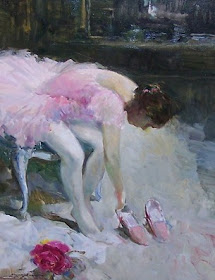

Las Zapatillas Rosa

And not everything he does are outdoors scenes.

[Scratches head, rubs chin] Oh dear. What to make of this. Well, the Giner Bueno paintings I saw were small compared to Sorolla's -- the latter's canvases could have propelled half the Spanish Armada.

Giner's paintings are competently done, and I'm pleased that a representational painter of his generation has made a successful career in the teeth of modernism. On the other hand, his work is just too similar to that of Sorolla for my taste; I see Giner and think Sorolla.

Then there is the Valencia factor, if indeed there is one, that might be called in Giner's support. I've never visited that corner of Spain, but can believe in the possibility that the scene is such that it can dominate any artist who attempts to depict it. Such is the case for California, where painters for the past 120-odd years have been producing paintings that are similar thanks to the subjects. (Though there is no California Impressionist whose work is dominant, unlike the case of Sorolla in Valencia.)

Friday, March 25, 2011

Asiatic Faces of the Fifties

Automobile styling has become considerably internationalized in recent decades. In the 1930s, 40s, 50s and even the 1960s American, English, French, German and Italian cars tended to have a national "look" or flavor. (Yes, I can cite exceptions, but I hope you can see my point.)

Nowadays young people from automobile-building countries can attend design schools in the USA, England and the continent, receiving comparable training. That is, the outcome is approximately the same regardless of country of origin or country of school. If a car design turns up with a strong national character, that's because it was the stylist's intention. A case in point was the original version of the Audi TT sports car which was styled by an American, yet somehow evokes German racing cars of the late 1930s.

National character was apparent in Asiatic vehicles of the late 1950s. Since few were exported to America and Europe, readers might not be aware of that was going on at that time and place, hence this post.

The Japanese automobile industry didn't begin taking off until the mid-1950s. Its cars were often derived from English models, and the designers were probably mostly home-grown. The result for a few years was cars with curiously fussy front ends. I say "curiously" because traditional Japanese architecture and painting tends to be rather spare and simple.

But -- who knows? -- I might well be totally wrong about all this. So give the pictures below a peek and decide for yourself.

Korean buses at Hongcheon, 1960

I found this image someplace on the web and was glad I did because it shows Korean buses as I remember them from my army days. Note that each one has a fussy grille that differs from the others. These grilles were probably cobbled together at the assembly point without the input of a trained designer.

Toyopet Crown

This is a Toyota from the mid-late 1950s. Whereas the grille design in general isn't greatly at odds with European or American styling practice of the time, its proportioning and execution are awkward and a tad fussy.

Toyopet Crown from the same era

The front end of this Toyota is tidier, but the design elements strike me as over-detailed for a car of its small size.

Nissan Prince Skyline ALSI-2 from around 1958

Another awkward design. Here we find round and rectangular elements that fight each other -- in particular, these round lights at the outer edges of the grille butting up against rectangular lights.

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Dialing It Back

I posted recently about my visit to the Arts Festival at La Quinta, California and mentioned that an artist's work gave enough food for thought to inspire a future article. Well, the future is now.

The artist was Beverly Wilson who paints bright California scenes that often include strong purple shadows, as can be seen in the picture below.

As mentioned in the earlier post, I thought the art show had an above-average quality level for that kind of event. And I'll add that I think Wilson was among the better painters there. However, I also think she goes a little too heavy when it comes to those purple shadows. Yes, it's a means to distinguish her paintings from the rest of the crowd, but the effect detracts a little from what her paintings might have been had she dialed back on the purple.

Sometimes an artist with a distinctive -- even highly marketable -- style should consider dialing back in the name of improved quality.

One artist who recently tried this is Michael Carson. Below are examples of his career-building style and recent works, a few of which I noticed in a gallery in Palm Desert, California about the same time I took in the Arts Festival.

Many of Carson's early paintings were party scenes containing people with exaggerated expressions.

Most of his paintings feature women. These are typical of his previous style: mural-style outlining, skin painted richly with occasional highlight spots as if the subjects had a slightly greasy surface.

I'm not sure of this, but these two paintings strike me as being transitional between the style seen above and his new style, below.

Recent Carsons have lost the bright, shiny skin surfaces. The brightness has faded towards gray. Highlight areas remain, but their impact is reduced thanks to the change of color key.

This painting is similar to what I saw in the Palm Desert gallery. More subtle skin color offset by stark blacks of the subject's clothing.

Carson's recent paintings are becoming a far cry from those early party scenes: he's done a lot of dialing back. To his benefit, I think.

Monday, March 21, 2011

David Stone Martin and His Scratchy Style

The 1950s and 60s saw major changes in mainstream illustration style. Conventional wisdom has it that photography began to force illustrators to move from highly representational style. For this and other reasons (advent of television, death of general-interest magazines, etc.), that's what indeed happened. And I'll suggest that part of this movement was to styles that tended to give the artist's medium increasing prominence and depiction of the subject matter less.

An artist who attained early success in this venture was David Stone (Livingstone) Martin (1913-1992) whose work was both avant-garde and a source of inspiration to art school students in the mid to late 50s. His Wikipedia entry is here and Leif Peng has a fine series of three articles about Martin at his Today's Inspiration blog dealing with early years, record jackets and general illustration.

My sense is that Martin isn't really considered an Old Master illustrator these days. Perhaps he's one of those respected borderline figures whose day will return at some point. Let's take a look at some of his stuff.

"Jazz at the Phil" cover

Lester Young cover

Muggsy Spanier cover

Drawing of Navy medics - c.1943

Schoolboys

Time cover - 26 August 1967

My take is complicated. That's because I really liked his work when it was new and I was young. Now I'm less sure. I'm still fond of his scratchy style of penwork -- the medium business I mentioned above. Although he made use of black spots as a counterpoise from the lines, they aren't nearly in the compositional use-of-black-league of, say, cartoons by Russell Patterson (go to Google or Bing images to find examples). Another way of looking at it might be to say that Martin's works were literally lightweight, though very nicely drawn. Regardless, he was an illustrator whose work should not be ignored.

Friday, March 18, 2011

Joseph Urban: Undersung Designer-Architect

Joseph Urban (1872-1933) is ever-so-slightly edging towards the design / architecture / theater history spotlight.

For example, this book about him appeared last year in conjunction with an exhibit. And this link is to an on-line catalog for a 2000 exhibit.

Urban was Viennese and rubbed elbows with Gustav Klimt, Kolo Moser and the rest of the artsy community during those wonderfully rich decades around the turn of the 20th century when Vienna was at its artistic peak. Like Moser, he was a jack of more than one trade, doing book illustration, theatrical set design and other tasks besides architecture, in which he was trained. Urban emigrated to the United States in 1912 (great timing, that) where he at first worked in theater before edging back into other fields.

He died not long after his 61st birthday having prevailed through the Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Moderne and early International Style eras. I have little doubt that he would have done well as a modernist had he lived another 20 years and into the postwar architectural boom.

Given his immense talent and adaptability, what puzzles me is why isn't Urban treated with greater honor in the annals of architecture and design?

My off the top-of-the-head reaction is that the Modernist Establishment didn't -- and still does not -- consider him to be seriously modernist. Too showy. Too decorative. And some other issues, no doubt. If you have suggestions, please comment. (I moderate comments, so it might take a while before they appear.)

Below are examples of Urban's work.

Gallery

Joseph Urban

Esterhazy Castle, Hungary, project - 1899

Rathauskeller, Vienna - 1899

Wiener Werkstätte shop, New York City - 1922

The Viennese design group tried to establish a New York beachhead in the early 1920s, but failed. That's a Gustav Klimt painting in the center.

Metropolitan Opera House design proposal - 1926-27

A number of architects, including Urban, were called in at various times during the planning and design of New York City's Rockefeller Center. Early plans had a new opera house facing Fifth Avenue, but this concept fell by the wayside. The Metropolitan Opera had to await new digs until 1966 when its Lincoln Center facility opened.

Ziegfeld Theatre, New York City - 1927

Designed by Urban and Thomas W. Lamb, the Ziegfeld was demolished in 1966 to make room for Burlington House, one of those dull glass-and-steel Sixth Avenue office towers. The Ziegfeld was looking a bit worn back in the early 1960s when I found myself walking past it.

Roof garden murals, St. Regis Hotel, New York City - 1927-28

Theatrical, but more 1900 than 1927. Maybe that's what the St. Regis thought its clients would like.

Hearst Building, New York City - 1928

Hearst Tower, New York City - 2006

Because Urban's original structure has protected status, Norman Foster and his gang decided to drastically contrast their high-rise addition with the 1928 base. Neither building is good architecture, so far as I'm concerned. But I also think that the Urban design makes for a better pedestrian experience than a foundation-to-top Foster version might well have been.

Auditorium, New School for Social Research - New York City, 1930

Here Urban shows his "streamlined modern" stuff.

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

I Saw the La Quinta Arts Festival -- And Survived!

I'm in the Palm Springs, California area while my wife is watching the tennis tournament at Indian Wells. I'm not at all into that game, so I'm keeping busy writing data display programs for my former employer (as a part-time employee till the end of June).

Saturday I took a break from the J computer language to take in the La Quinta Arts Festival, an event the sponsors tout as Number Three in the USA.

I don't often do art fairs because usually I don't find much of interest. But as I mentioned, I needed some diversion, so I arrived early to find a free parking lot, grabbed a coffee and Wall Street Journal at a fine coffee house in the Old Town, then waited in line and finally plunked down the $12 admission fee to enter. I spent about an hour there and took some photos to document what I saw. A selection is below.

The artists came from as far north as Washington's San Juan Islands and as far east as Florida. I estimate that most fall into the category of having some gallery representation, yet have yet to become well-known to the art consumption public. The quality was a notch above what one might find at a local art fair, so someone with a four-figure budget wanting a nice decorative piece for the family room could do well at the La Quinta.

Gallery

This is the setting -- a park in the La Quinta Old Town near City Hall. Those white tents house each artist's wares.

There were sculpture, woodwork, photography and other items besides paintings.

Some painting was abstract. I think the ones pictured here would make a decent decoration in an appropriately furnished room.

This artist seems to be able to supply several genres, but nothing that lit my fire.

This group is cartoony and rather silly, so far as I'm concerned. I wonder who buys this stuff and, more importantly, why.

If Botero can make a mint painting fat people, others will be willing to enter that game.

On the more representational side, here in desert country paintings of Indians can sell.

The artist in this tent does it all with palette knives; I saw him at work on a new painting. Poor me, I lack the imagination to appreciate what he's doing. I understand using a knife to do bits of a painting where appropriate. But the whole thing? ... Sorta like inscribing the Lord's Prayer on the head of a pin; a marvel of sorts, but to what other purpose?

The French Impressionists made purple shadows respectable. This artist uses them a whole lot. This inspires me to write a post, but not necessarily about shadows.

Here is Michael Situ's tent. He tells me he's no relation of the increasingly famous Mian Situ, though both work out of the Laguna Beach area. That might be his wife in the foreground. The paintings are mostly plein air studies, but very nice and more finished than studies often tend to be.

Monday, March 14, 2011

General Motors Aerotrain: A Rider's Report

The photos above are of General Motors' Aerotrain, a mid-1950s attempt to put pizazz into rail travel and sell many similar locomotive-and-coaches combinations to America's ailing passenger railroads.

The Wikipedia entry here and this fuller account summarize the disappointing (to GM) tale of railroads that tried the demonstrator trains but refused to buy any production versions.

Basically, the Aerotrain was a flashy, automobile-styled locomotive pulling a string of coaches using some of the body stampings from inter-city buses GM was building at the time. By the way, that automobile reference is more real than one might think: the guy behind the design was Chuck Jordan, who many years later went on to head GM's styling operations.

The Aerotrain interests me because I actually rode one. I was a school kid at the time, and my dad bought a new DeSoto and we were traveling from Seattle by train to pick up the car at the factory. After stopping in Chicago to visit relatives, we took the New York Central to Detroit (the Wikipedia entry doesn't mention this run, the second link does), and lo! we got to ride the Aerotrain.

In retrospect, the best part of the trip was the green-uniformed, red-haired Southern stewardess who looked at totally blushing me with big blue eyes and asked if y'all needed anything.

The worst part, as both links mention, was the rough ride. An unusual suspension design is cited as the culprit. Maybe so. But I always thought the problem was that the bus-based coaches were simply too light. In any case, trying to walk while the train was at speed was difficult due to random lurching and bouncing.

Sometimes transportation concepts of the future have no future.

Friday, March 11, 2011

Robert Fawcett Biography

Robert Fawcett (1903-1967) was a highly respected illustrator who, perhaps due to his color-blindness, usually worked in black inks and compatible media. His major strengths were draftsmanship and composition supported by skill in doing the research needed to get details right.

Illustration-buff blog readers are probably already aware that a major

biography of Fawcett rolled off the presses not long ago (see cover image above). Although late to the scene owing to the fact that I got my copy only a week or so ago, this post is my brief review. (Fawcett has been getting a nice share of attention recently in addition to the book. For example, there was an exhibit of his work last year; Charley Parker mentions it here and includes some biographical information.)

Most of the biography is actually a substantial collection of Fawcett's work. There is a text supplied by the popular illustration blogger David Apatoff who mentions the book in this post.

Since Apatoff does very good work, I was pleased with what I read, but wanted more, more! I'm usually interested in human and situational factors in art almost as much as the art itself, provided such information is available. The comparatively limited amount of verbiage might have been due to (1) the publisher's desire to maximize the pictorial content within the book's page budget -- a reasonable choice -- or (2) David simply wasn't able to locate much information about Fawcett -- a real possibility given that the man died nearly 45 years ago.

As for Fawcett himself, he claimed to have studied neither anatomy nor perspective. Rather, he said that he learned to observe very carefully, and the ability to draw what he saw was sufficient for operating on the level he did. I wonder. Whereas I'm pretty sure that he couldn't name many bones and muscles, I doubt that he was naive regarding artistically important things going on "under the skin" so to speak. Moreover, I find it hard to believe that he didn't understand perspective up to and including the three-point variety. Perhaps he couldn't work out the details mechanically as an architect might, but he knew how to closely "fake" it.

Skilled as he was, Fawcett sometimes rushed his jobs. Here and there in the book I found featured male figures (usually clad in suits) that appeared stiff and simplified. The illustration below tends in that direction, but isn't as extreme as a few cases in the book.

This is not to criticize Fawcett; many of his illustrations were prodigiously detailed and superbly executed. Still, he was a busy man in the 1940s and 50s and needed to keep bread on his table, so occasionally he seems to have rushed things. It's these odd details of his thinking and work that make the book so interesting.