A blog about about painting, design and other aspects of aesthetics along with a dash of non-art topics. The point-of-view is that modernism in art is an idea that has, after a century or more, been thoroughly tested and found wanting. Not to say that it should be abolished -- just put in its proper, diminished place.

Monday, September 28, 2015

Gustav Klimt's Houses at Unterach on the Attersee

The painting shown above is Häuser in Unterach am Attersee (Houses at Unterach on the Attersee) painted around 1916 by Gustav Klimt (1862-1918). He often summered in the Austrian lake district even while the Great War was raging It has been theorized that Klimt used a telescope for this view; the perspective certainly is flattened in the manner of a telephoto lens image. Biographical information on Klimt can be found here.

The approximately meter-square painting was auctioned at Christies in New York City on 8 November 2006. The pre-auction estimate was $18-25 million, but it sold for $31,376,000.

It was one of a group of Klimt paintings owned by the Bloch-Bauer family that were confiscated by the Nazis following the 1938 Anschluss. After the war they were in the hands of the Austrian government and displayed in Vienna's Belvedere where I saw some in the late 1990s. A descendent of the family sued for their return, and eventually succeeded. Thereafter, they were sold, as mentioned here (scroll down).

The last time we were in Vienna, my wife and I stopped by the Österreichische Werkstätten (Austrian Workshops), Kärntner Strasse 6, 1010 Wien, Österreich and spotted serigraphs of the painting. We decided to buy one the next day, but by then the rolled-up version had been sold and what remained was the serigraph attached to a stretcher. The cost of shipping it to Seattle was about the same as that of the serigraph itself, so I later wrapped it and it managed to survive the air trip home. It was properly framed and now hangs over our fireplace.

Thursday, September 24, 2015

Mr. Munch and Mrs. Schwarz

In July I was working my way through the Edvard Munch (1863-1944) portion of the Rasmus Meyer collection at the Bergen, Norway Kunstmuseet when I noticed the painting that I then immediately photographed (see above). It is a portrait study of Mrs. (Fru in Norwegian, Frau in German) Helene Schwarz, made in 1906 when Munch was in Berlin.

I am ambivalent regarding Munch, who I wrote about here. I'm not fond of most of his work, but acknowledge that he was capable of drawing and painting in reasonable and interesting ways at times -- mostly early in his career. I consider his Schwarz series among his better efforts.

He made at least three versions of Mrs. Schwarz that survive, all done in 1906; they are shown below. But it wasn't until 2013 that the identity of Mrs. Schwarz was provisionally found. The account is here. It seems that Helene Schwarz was the wife of Georg Schwarz, a consultant to the Cassirer art gallery in Berlin. Before marrying him, she served as a companion to Ernst and Toni Cassirer. It also seems that Georg wanted to buy the final painting, but Munch refused the offer and eventually sold it in Norway.

An image of the above portrait study found at the The Athenaeum website (scroll down).

A drawing or lithographic print of Mrs. Schwarz.

The final portrait painting.

A photograph of Mrs. Schwarz (at right) with her son Andreas and perhaps a nanny.

Monday, September 21, 2015

Coping With the Great Depression: John Newton Howitt

Note: I drafted this on 13 June for later posting. Now it turns out Illustration Magazine's just-released Issue No. 49 has a large article on John Newton Howitt. Below is what I wrote in June regarding Howitt.

* * * * *

John Newton Howitt (1885-1958) is an illustrator not widely known these days. But I'd place him in the "successful" category because he made the American illustration Big Time by doing occasional cover art for the Saturday Evening Post, the leading general-interest magazine in his time.

A reasonably detailed biographical sketch can be found here, a Web site devoted to illustrators working for "pulp" magazines. Printed on cheap, pulp (thick, with rough surfaces) paper, they flourished during the Great Depression of the 1930s specializing in fiction topics such as crime, science-fiction, cowboys, romance, terror, adventure and such.

So what was an illustrator for "slick" (smooth, quality paper) magazines such as the Post doing in the pulp field? He was trying to maintain his livelihood during the Depression, and the pulp market was doing well thanks to escapist subjects and cheap news stand prices. Some better-known illustrators such as Tom Lovell and Walter Baumhofer got their start in pulps, eventually graduating to the slicks. So Howitt was an exception, doing slicks work before and after the Depression and pulps and the occasional slick during those trying years.

Howitt signed his Fine Art and slicks illustrations with his full name. His pulp work either wasn't signed at all or else he simply used the initial "H" to identify it. Apparently many of the originals of his pulp work were destroyed. One source stated the Howitt himself did it, another claims it was his wife.

Gallery

Buried Treasure - (Cream of Wheat breakfast cereal advertisement) - 1909

The Symphony - ca. 1925

This might be a Fine Arts painting, but could just as well be art for advertising radios.

Probably a Fine Arts painting - 1910s?

Mother and children illustration - late 1920s

Farm family - probably an illustration from the 1930s

Holland's Magazine cover - May, 1929

Horror Stories cover - January 1935

\

Terror Tales cover - November 1935

Howitt's work was noticeably better than that found on many pulp covers (Baumhofer and a few others excepted).

Saturday Evening Post cover, 20 September 1936

Saturday Evening Post cover, 19 October 1940

The joke here is that the sailor sees a photo of a soldier (!!!) falling out of the purse.

John Newton Howitt (1885-1958) is an illustrator not widely known these days. But I'd place him in the "successful" category because he made the American illustration Big Time by doing occasional cover art for the Saturday Evening Post, the leading general-interest magazine in his time.

A reasonably detailed biographical sketch can be found here, a Web site devoted to illustrators working for "pulp" magazines. Printed on cheap, pulp (thick, with rough surfaces) paper, they flourished during the Great Depression of the 1930s specializing in fiction topics such as crime, science-fiction, cowboys, romance, terror, adventure and such.

So what was an illustrator for "slick" (smooth, quality paper) magazines such as the Post doing in the pulp field? He was trying to maintain his livelihood during the Depression, and the pulp market was doing well thanks to escapist subjects and cheap news stand prices. Some better-known illustrators such as Tom Lovell and Walter Baumhofer got their start in pulps, eventually graduating to the slicks. So Howitt was an exception, doing slicks work before and after the Depression and pulps and the occasional slick during those trying years.

Howitt signed his Fine Art and slicks illustrations with his full name. His pulp work either wasn't signed at all or else he simply used the initial "H" to identify it. Apparently many of the originals of his pulp work were destroyed. One source stated the Howitt himself did it, another claims it was his wife.

Buried Treasure - (Cream of Wheat breakfast cereal advertisement) - 1909

The Symphony - ca. 1925

This might be a Fine Arts painting, but could just as well be art for advertising radios.

Probably a Fine Arts painting - 1910s?

Mother and children illustration - late 1920s

Farm family - probably an illustration from the 1930s

Holland's Magazine cover - May, 1929

Horror Stories cover - January 1935

\

Terror Tales cover - November 1935

Howitt's work was noticeably better than that found on many pulp covers (Baumhofer and a few others excepted).

Saturday Evening Post cover, 20 September 1936

Saturday Evening Post cover, 19 October 1940

The joke here is that the sailor sees a photo of a soldier (!!!) falling out of the purse.

Thursday, September 17, 2015

Architects' Homes: The "Harvard Five"

I find the houses architects design for themselves interesting. Presumably, the constraint of catering to the desires of a client are swept away so that the architect can express his own design philosophy and personality.

Other constraints remain, of course. The nature of the site, the cost of building the house and the needs of the architect's family can be factors. Then there is the possibility that the architect wishes the house to be a professional advertisement, to be featured in local newspapers or even architectural magazines.

The present post features personal houses designed by a group of architects called the Harvard Five. They were associated with Harvard University in one way or another and settled in New Canaan, Connecticut where their houses were built. They were born between 1902 and 1919 and the houses were built from 1949 to 1958, so we are dealing with a group having a fairly homogeneous background. The houses reflect avant-garde domestic design in the United States from 1945 to around 1955 when the designs were conceived.

Modernist and postmodern architects have done a good deal of damage, in my judgment. But the worst of it is in the form of large buildings and not so much houses, where modest size means less visual impact. The Harvard Five houses are situated on large lots, fairly isolated from neighbors.

Shared design characteristics include large expanses of window glass, a byproduct of 20th century heating technology that eliminated the need to build tall houses with small windows and compact rooms each with a fireplace. They have flat roofs (or nearly so), an architectural fad contradicting the "form follows function" concept (flat roofs shed water and snow less well than gabled roofs). None feature explicit ornamentation. All but one are single-story.

Gallery

Marcel Breuer House - 1949

Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) had Bauhaus associations that continued through the 1930s in the person of Walter Gropius. There seems to be a whiff or decorative intent in the angled paneling on some of the walls.

Landis Gores House - 1948

Landis Gores (1919-1991) was stricken with polio, yet managed to continue his career. The use of stonework on some of the walls is a nod to the New England environment and also helps to offset the stark, geometrical aspects of the design.

John M. Johansen House - 1958

John M. Johansen (1916-2012) used a formal (symmetrical) floor plan where four sub-structures were attached to this creek-spanning central unit near its corners. Roofs are flat aside from the part featured in the photo.

Philip Johnson House - 1953

This house by Philip Johnson (1906-2005) is by far the most famous and controversial. Controversial due to its apparent lack of privacy. I consider it a case of an architectural theory pushed beyond the realm of common sense.

Eliot Noyes House - 1955

Eliot Noyes (1910-1977) is perhaps better known for his industrial design and corporate image work than for his architecture. Like Gores, he used local stone in his house's construction. But he did this in a more rigid way, essentially blanking out two walls of the building in stark contrast to the glazing of the side facing the camera in this photo. Like Johnson's house, this strikes me as being an instance of being too clever, resulting in degraded livability.

Other constraints remain, of course. The nature of the site, the cost of building the house and the needs of the architect's family can be factors. Then there is the possibility that the architect wishes the house to be a professional advertisement, to be featured in local newspapers or even architectural magazines.

The present post features personal houses designed by a group of architects called the Harvard Five. They were associated with Harvard University in one way or another and settled in New Canaan, Connecticut where their houses were built. They were born between 1902 and 1919 and the houses were built from 1949 to 1958, so we are dealing with a group having a fairly homogeneous background. The houses reflect avant-garde domestic design in the United States from 1945 to around 1955 when the designs were conceived.

Modernist and postmodern architects have done a good deal of damage, in my judgment. But the worst of it is in the form of large buildings and not so much houses, where modest size means less visual impact. The Harvard Five houses are situated on large lots, fairly isolated from neighbors.

Shared design characteristics include large expanses of window glass, a byproduct of 20th century heating technology that eliminated the need to build tall houses with small windows and compact rooms each with a fireplace. They have flat roofs (or nearly so), an architectural fad contradicting the "form follows function" concept (flat roofs shed water and snow less well than gabled roofs). None feature explicit ornamentation. All but one are single-story.

Marcel Breuer House - 1949

Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) had Bauhaus associations that continued through the 1930s in the person of Walter Gropius. There seems to be a whiff or decorative intent in the angled paneling on some of the walls.

Landis Gores House - 1948

Landis Gores (1919-1991) was stricken with polio, yet managed to continue his career. The use of stonework on some of the walls is a nod to the New England environment and also helps to offset the stark, geometrical aspects of the design.

John M. Johansen House - 1958

John M. Johansen (1916-2012) used a formal (symmetrical) floor plan where four sub-structures were attached to this creek-spanning central unit near its corners. Roofs are flat aside from the part featured in the photo.

Philip Johnson House - 1953

This house by Philip Johnson (1906-2005) is by far the most famous and controversial. Controversial due to its apparent lack of privacy. I consider it a case of an architectural theory pushed beyond the realm of common sense.

Eliot Noyes House - 1955

Eliot Noyes (1910-1977) is perhaps better known for his industrial design and corporate image work than for his architecture. Like Gores, he used local stone in his house's construction. But he did this in a more rigid way, essentially blanking out two walls of the building in stark contrast to the glazing of the side facing the camera in this photo. Like Johnson's house, this strikes me as being an instance of being too clever, resulting in degraded livability.

Monday, September 14, 2015

Adolph Menzel: Tiny Works from a Tiny Man

Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel (1815-1905) -- the "von" bestowed late in his career -- was very popular in his day and honored by the Kaiser upon his death. These accolades were deserved, because Menzel was highly skilled, his drawings perhaps being more likable than his painted works.

His Wikipedia entry is here. It's fairly brief, but notes two interesting and likely related facts aside from mentioning that his formal art training was limited. One fact is that he was only about four and a half feet tall. The other is that while he enjoyed society, he was emotionally detached, especially so far as women were concerned.

Besides being very short, many of his works also were of small size, more a curiosity than a connection. Probably he was a natural miniaturist like Meissonier, Dalí and others. Below are some of his small-format works.

Gallery

At the Louvre - 1867 (9.3 x 7.1 in.)

Hard to tell if this is a small study or a finished work just by looking at it. However, Menzel considered it finished because he signed it.

Baron von der Heydt, Minister of State - 1864 (11.65 x 8.8 in.)

Although the format is not large, the image is only slightly less than life-size, typical of most portraits.

Meissonier in his Studio at Poissy - 1869 (9 x 11.5 in.)

Meissonier also liked to work small, though the painting seen at his easel is fairly normal-size.

Princess Alexandrine of Prussia - ca. 1863-64 (11.6 x 9 in.)

A study about the size of a news magazine cover.

Soldier of the Prussian Landwehr and French Prisoners - 1871 (8.3 x 7.8 in.)

This is unfinished, though it seems odd that the left-hand 60 % is almost complete and all the remainder is roughly blocked in.

The Artist's Foot - 1876 (15.2 x 13.2 in.)

The depicted foot is close to actual size.

Weekday in Paris - 1869 (19 x 27.4 in.)

This painting is larger than the others, but the details are quite small.

His Wikipedia entry is here. It's fairly brief, but notes two interesting and likely related facts aside from mentioning that his formal art training was limited. One fact is that he was only about four and a half feet tall. The other is that while he enjoyed society, he was emotionally detached, especially so far as women were concerned.

Besides being very short, many of his works also were of small size, more a curiosity than a connection. Probably he was a natural miniaturist like Meissonier, Dalí and others. Below are some of his small-format works.

At the Louvre - 1867 (9.3 x 7.1 in.)

Hard to tell if this is a small study or a finished work just by looking at it. However, Menzel considered it finished because he signed it.

Baron von der Heydt, Minister of State - 1864 (11.65 x 8.8 in.)

Although the format is not large, the image is only slightly less than life-size, typical of most portraits.

Meissonier in his Studio at Poissy - 1869 (9 x 11.5 in.)

Meissonier also liked to work small, though the painting seen at his easel is fairly normal-size.

Princess Alexandrine of Prussia - ca. 1863-64 (11.6 x 9 in.)

A study about the size of a news magazine cover.

Soldier of the Prussian Landwehr and French Prisoners - 1871 (8.3 x 7.8 in.)

This is unfinished, though it seems odd that the left-hand 60 % is almost complete and all the remainder is roughly blocked in.

The Artist's Foot - 1876 (15.2 x 13.2 in.)

The depicted foot is close to actual size.

Weekday in Paris - 1869 (19 x 27.4 in.)

This painting is larger than the others, but the details are quite small.

Thursday, September 10, 2015

Illustrations by Fish

Anne Harriet Fish Sifton (1890-1964), is best known as "Fish" -- that's her maiden name and how she usually signed her cartoons and illustrations. She was English, but well known in the United States due to her cover art and cartoons in Vanity Fair magazine. Biographical information is sketchy, but various bits of information can be found here, here and here.

Her style included considerable simplification and exaggeration of the human form, but in the interests of overall image design and emphasizing her witty take on high society with its all-too-human undertones. It's interesting that this style that strikes us today as being very 1920s was actually present by around 1915.

Some images below are copyrighted by Condé Nast publications; it seems they will be happy to sell you prints of Vanity Fair covers by Fish.

Gallery

Photo of Anne Fish

Vanity Fair cover - November, 1916

Vanity Fair cover art (detail) - December, 1921

Awful Weekends (part of a series)

Click to enlarge so that captions can be read.

Vanity Fair cover - February, 1926

Vanity Fair cartoon workup (via Bonhams) - 1923

Abdulla cigarettes ad art - 1927

Her style included considerable simplification and exaggeration of the human form, but in the interests of overall image design and emphasizing her witty take on high society with its all-too-human undertones. It's interesting that this style that strikes us today as being very 1920s was actually present by around 1915.

Some images below are copyrighted by Condé Nast publications; it seems they will be happy to sell you prints of Vanity Fair covers by Fish.

Photo of Anne Fish

Vanity Fair cover - November, 1916

Vanity Fair cover art (detail) - December, 1921

Awful Weekends (part of a series)

Click to enlarge so that captions can be read.

Vanity Fair cover - February, 1926

Vanity Fair cartoon workup (via Bonhams) - 1923

Abdulla cigarettes ad art - 1927

Monday, September 7, 2015

Edward Durell Stone: In and Out and Maybe In Favor Again

Edward Durell Stone (1902-1978) had a successful career in terms of the number of projects with which he and his firm were associated. Scroll down this Wikipedia entry for a list of some of them. More biographical information can be found here.

Stone first made his mark designing modernist houses during the Depression years. His reputation was enhanced due to his work on the new headquarters of New York's Museum of Modern Art (since replaced). Modernism having become the official religion of professional architecture, Stone was riding high professionally.

Then came the mid-1950s when he began covering some of his buildings with geometrically pattered screens and even (gasp!!) adding such ornamental detail on the actual exteriors. The Architecture establishment was shocked at such regression, but by then Stone was famous enough that commissions kept coming.

By the 1970s his firm was back to designing more acceptably modernistic buildings.

Gallery

Conger-Goodyear House, Old Westbury Long Island - 1938

This Ezra Stoller photo shows one of his modernist houses.

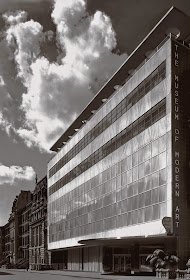

Museum of Modern Art, New York City - 1939

Designed in association with Philip Goodwin, the MoMA building had a few curved details (the entry overhang and piercings in the roof), faint echoes of some of Frank Lloyd Wright's thoughts.

Stone House Façade, New York City - 1956

Stone's East Sixties house fronted by one of his new screens.

U.S. Embassy, New Delhi - 1954-59

This was the screened building that caught the world's attention and helped make Stone known to the public at large.

Home Savings / Perpetual Savings, Los Angeles - 1962

Photo of the architectural model.

2 Columbus Circle (Gallery of Modern Art), New York - 1964

Commissioned by Huntington Hartford, this was a museum featuring representational art that failed to compete agains the modernist art tide. The exterior was unusual, being largely blank with decorative openings around the edges. The non-rectangular openings towards the top were unconventional, but the decorative posts at the bottom were in synch with what Minoru Yamasaki was doing in Seattle at that time. I was in the building once, now dimly recalling that the interior layout seemed cramped and confusing. The building has been drastically renovated for other uses.

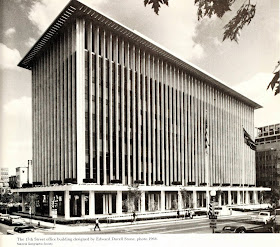

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C. - 1964

Here Stone reverted to classic Greek column elements: base, middle and cap (in the form of a bold cornice).

State University of New York, Albany - 1964-64

Here Stone and his design team ignored human factors. I spent more the four years in the Albany area in the early 1970s and visited the SUNY campus fairly often to use the library. In those days (and perhaps still) doors were opened by grasping squared metal bars -- an unpleasant experience if you weren't wearing gloves. I also recall that it was an inconvenient grouping to navigate, something related to the fact that most of the buildings were linked at ground level. That was to provide shelter during the frigid part of the school year, a worthy aim not well carried out. I rate the SUNY project a failure.

Standard Oil Building, Chicago - 1970-74

Finally back to a more purely modernist style late in Stone's career.

Stone first made his mark designing modernist houses during the Depression years. His reputation was enhanced due to his work on the new headquarters of New York's Museum of Modern Art (since replaced). Modernism having become the official religion of professional architecture, Stone was riding high professionally.

Then came the mid-1950s when he began covering some of his buildings with geometrically pattered screens and even (gasp!!) adding such ornamental detail on the actual exteriors. The Architecture establishment was shocked at such regression, but by then Stone was famous enough that commissions kept coming.

By the 1970s his firm was back to designing more acceptably modernistic buildings.

Conger-Goodyear House, Old Westbury Long Island - 1938

This Ezra Stoller photo shows one of his modernist houses.

Museum of Modern Art, New York City - 1939

Designed in association with Philip Goodwin, the MoMA building had a few curved details (the entry overhang and piercings in the roof), faint echoes of some of Frank Lloyd Wright's thoughts.

Stone House Façade, New York City - 1956

Stone's East Sixties house fronted by one of his new screens.

U.S. Embassy, New Delhi - 1954-59

This was the screened building that caught the world's attention and helped make Stone known to the public at large.

Home Savings / Perpetual Savings, Los Angeles - 1962

Photo of the architectural model.

2 Columbus Circle (Gallery of Modern Art), New York - 1964

Commissioned by Huntington Hartford, this was a museum featuring representational art that failed to compete agains the modernist art tide. The exterior was unusual, being largely blank with decorative openings around the edges. The non-rectangular openings towards the top were unconventional, but the decorative posts at the bottom were in synch with what Minoru Yamasaki was doing in Seattle at that time. I was in the building once, now dimly recalling that the interior layout seemed cramped and confusing. The building has been drastically renovated for other uses.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C. - 1964

Here Stone reverted to classic Greek column elements: base, middle and cap (in the form of a bold cornice).

State University of New York, Albany - 1964-64

Here Stone and his design team ignored human factors. I spent more the four years in the Albany area in the early 1970s and visited the SUNY campus fairly often to use the library. In those days (and perhaps still) doors were opened by grasping squared metal bars -- an unpleasant experience if you weren't wearing gloves. I also recall that it was an inconvenient grouping to navigate, something related to the fact that most of the buildings were linked at ground level. That was to provide shelter during the frigid part of the school year, a worthy aim not well carried out. I rate the SUNY project a failure.

Standard Oil Building, Chicago - 1970-74

Finally back to a more purely modernist style late in Stone's career.

Thursday, September 3, 2015

Alfred Stevens: Combining Hard-Edge and Brushy Styles

Alfred Émile Léopold Stevens (1823-1906) was a Belgian whose family was heavily involved in the arts, as this Wikipedia entry explains. Paris being a far more important art center than Brussels, Stevens went there for training and spent most of his long and largely successful career there.

He was in his late 40s and 50s when Impressionism came on the scene, though freely-brushed paintings had appeared before then. In any case, Stevens, whose favorite subjects were elegant women, was a painter quite capable of working in both tight and free styles. I hadn't given this any though until I noticed the following painting on the Internet.

Looking Out To Sea - ca. 1890 The women is painted in a tight, "finished" manner, whereas the seascape in the background is painted in a free, almost-Impressionist style with a late-Turner feel. The only date for it that I could find had it painted around 1890. I'll assume that is so, for now. The images below are of some paintings he did in various styles earlier in his career that, if the 1890 date is about right, indicate a path to its achievement.

Gallery

In the Country - c. 1867

Stevens was in his early 40s when he did this. The woodsy background is dark, but not painted very tightly, as is so for the foreground subject.

After the Ball (Confidence) - 1874

An interior scene painted when Stevens was about 50. Tightly done: notice the fabric detail on the dresses.

Sarah Bernhardt - 1882

The famed actress took painting lessons from Stevens when he was in his early 60s. In return, he painted her several times. Here most of it is painted in a rather feathery brush style, sharpened here and there. Interestingly, the more tightly-painted fan seems more the main subject rather than Bernhardt's face. (But yes, we are still drawn to her eyes.)

Elegant on the Boulevards - 1888

This is done in a free, almost sketchy manner. Something like the sea background in the first painting.

He was in his late 40s and 50s when Impressionism came on the scene, though freely-brushed paintings had appeared before then. In any case, Stevens, whose favorite subjects were elegant women, was a painter quite capable of working in both tight and free styles. I hadn't given this any though until I noticed the following painting on the Internet.

In the Country - c. 1867

Stevens was in his early 40s when he did this. The woodsy background is dark, but not painted very tightly, as is so for the foreground subject.

After the Ball (Confidence) - 1874

An interior scene painted when Stevens was about 50. Tightly done: notice the fabric detail on the dresses.

Sarah Bernhardt - 1882

The famed actress took painting lessons from Stevens when he was in his early 60s. In return, he painted her several times. Here most of it is painted in a rather feathery brush style, sharpened here and there. Interestingly, the more tightly-painted fan seems more the main subject rather than Bernhardt's face. (But yes, we are still drawn to her eyes.)

Elegant on the Boulevards - 1888

This is done in a free, almost sketchy manner. Something like the sea background in the first painting.