A blog about about painting, design and other aspects of aesthetics along with a dash of non-art topics. The point-of-view is that modernism in art is an idea that has, after a century or more, been thoroughly tested and found wanting. Not to say that it should be abolished -- just put in its proper, diminished place.

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

Artists and Writers Time-Warped

The Wall Street Journal's Joe Morgenstern liked it, John Podhoretz at The Weekly Standard didn't (no link available). Me? I seldom go to movies. But when I do, it's usually because of the concept or subject. The last Woody Allen movie I remember seeing was his 1975 "Love and Death," demonstrating that I'm not a big fan. But his latest flick, "Midnight in Paris" (IMDb link here) intrigued me due partly to its time-travel gimmick and mostly because it includes writers and artists of Paris in the 1920s, a period I've read a fair amount about (that's the movie's Zelda Fitzgerald at the left in the photo above). So I went.

Read Morgenstern's review for details about the movie. I'll just name-drop. There are major speaking parts for Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein, lesser ones for Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí (who is obessing on the concept of "rhinoceros"), Luis Buñuel (in need of movie ideas), Man Ray, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald (she attempts suicide at one point), T.S. Eliot, Henri Matisse, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas (the last three in a secondary time-warp), and a singing part for Cole Porter.

The casting director did a good job finding actors who could be made up to look a lot like the originals. Since you can't win 'em all, there were some compromises. For example, Picasso might have been a bit too tall and slender, and Man Ray definitely was too tall. But you watch it and find more near-misses, though that probably won't interfere with your experience.

A character in the 2010 part of the movie is a know-it-all who disputes facts with the guide at the Rodin museum; that one hit pretty close to home. The guide, by the way, was played by France's femme No. 1, Carla Bruni.

There also were some temporal ambiguities. Hemingway was encountered after his first novel (1926) but before he wrote much more. Dalí was in Paris in 1926, but Surrealism was largely a literary movement at that time, its better-known painting/visual aspect was only starting to emerge even though much is made of it in the movie. Those points and others make it difficult to pin down just when in the 20s the action takes place. But again, that's minor because Allen is trying to evoke a short, rich era rather than any particular time within it.

So if you like arts and letters and have more than passing knowledge of Paris and the 1920s, you'll likely find much in this movie to enjoy.

Monday, June 27, 2011

Renault Streamlined Cars - 1934

I wrote about automobile streamlining in both the technical and stylistic senses here and here. Now I'd like to mention a body style introduced by Renault at the October 1934 Paris auto show that was a first tangible step in the streamlining direction, a step roughly in line with what a few American manufacturers were doing at the time. (I exclude the larger step made by Chrysler with its Airflow that was introduced for the 1934 model year.)

I said "tangible step" because effort was made to go beyond essentially cosmetic streamlining features such as fender skirts and slightly inclined radiator grilles such as appeared a year or two earlier; I'll explain in the photo captions below.

One side-detail I find interesting is the fact that Renault was able to afford to put these changes into production, given their total output in those days -- about 55-60,000 cars per year. And that production was divided amongst three different body/chassis types: the low-end "Quatre," the mid-high range "Stella," "Nerva" and "Viva" lines (variations on the same package) and the semi-streamlined "Grand Sport" shown below. I don't have enough data at hand, so my guess is that French cars, small and large, were relatively more expensive than American equivalents. Otherwise, how could Renault and other firms remain in business and keep up with the technological and styling theme times?

Let's look at the Renault Grand Sports that were designed in 1933 or thereabouts.

Gallery

Here's a 1935 Nerva Grand Sport at one of the concours popular in France at the time. Note the sloped, V'd windshield, the sloped grille and the blending of the headlights into the fenders. These features surely improved aerodynamic efficiency somewhat. The sides of the car had partial streamlining despite what the swoopy fender line might suggest.

Another concours, this featuring a convertible version of the Grand Sport (note the English spelling of "Grand").

This side view shows that even though traditional fender profiling was preserved, fenders and running boards were in low relief compared to nealy all contemporary automobiles.

The view from above is useful because it shows that the front, hood and top were indeed noticeably more aerodynamically efficient than previous designs featuring vertical fronts, detached headlights and so forth.

This is a fragment of a publication I include to show what the rear windows looked like. Click to enlarge.

Compare the Renault to this 1935 Hupmobile. The Hupp also features embedded headlights and a sloping grille and windshield. However, the latter is a three-pane "wraparound" style rather than a two-pane vee. The sides of the Hupp are high-relief, typical styling practice until near the end of the decade.

This is Studebaker's Land Cruiser for 1934. Its curved rear and multi-pane back window design is in advance of nearly all 1934 competition and in the same spirit as the Renault. The rest of the car is conventional.

Friday, June 24, 2011

Harry Beckhoff: Starting Small

When I'm out having a cup of coffee I usually grab four or five extra paper napkins to make use of while I'm sipping. Sometimes I'm making lists of potential blog topics or, if I already have a subject in mind, I might outline or list items I could include.

Other times, I might sketch car designs or poses nearby people assume. And I've found that fine-point ball point pens work just fine on napkins provided there is more than one napkin layer (some cushioning helps prevent the pen from gouging through the paper).

These drawing are small, seldom exceeding two inches (5 cm) in the longest direction. And because they're small, I can't get hung up with details -- a good practice that counteracts tendencies to make images more "complete" than they should be.

Harry Beckhoff (1901-1979) was an illustrator who worked in thumbnail sketch mode. He didn't make large, sweeping-gesture sketches and then boil them down to production size. Instead, he had his thumbnails enlarged and then traced them as the basis for the final job.

Leif Peng mentions this unconventional practice in this post about Beckhoff. Another take on him is here. Otherwise, there seems to little information about him on the Internet.

I find Beckhoff's work charming, and hope you too will like the following examples.

Gallery

This is the only thumbnail I could discover on the Web, but it gives us a pretty good idea of what Beckhoff was up to.

Nearly everything he did had a touch of humor. This was supported by his technique which was a blend of cartooning and straight illustration.

I don't have titles for most of the examples, so I'll invent my own where I can. This one I call "Snow-Fallen."

Here Beckhoff presents an interest dramatic situation: fill in the blanks.

Perhaps this is half of a spread, but it still works as an illustration.

This is a 1950 illustration for a Collier's story titled "The Third Level." It shows New York's Grand Central Terminal with one fellow 40 years out of synch with the other fashions. Might have been an interesting story.

Here's a early 1940s vintage illustration I'll call "Running Late."

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

Kroyer's Tranquil Denmark

Denmark has been an essentially tranquil place since Lord Nelson turned his blind eye to his commander's signal flags and devastated the Danish fleet at Copenhagen. Even the German invasion of April, 1940 was nearly bloodless.

So too was the work of one of Denmark's most famous painters, Peder Severin Krøyer (1851-1909). His Wikipedia entry notes that he was born in Norway to an unstable women and a nameless father, dying in Copenhagen aged 58 of the effects of syphilis after becoming largely blind. Perhaps that disease coupled with his own unstable personality drove his beautiful, talented wife Marie into the arms of another man and divorce from the painter. Although Denmark may be tranquil, it seems not all Danish lives follow suit.

Nevertheless, Krøyer's subjects centered on portraits, beach scenes and social get-togethers of various kinds, often set in Skagen, an artist summer colony town at the northern tip of the Jutland peninsula in mainland Denmark.

I find Krøyer's paintings skilfully done and pleasant. They don't interest me much beyond that, but perhaps you might like some of them; take a look at this sampling.

Gallery

Sommeraften på Skagen Sønderstand - Summer evening on the Skagen beach - 1895

This is perhaps Krøyer's most famous work.

Hip, hip, hurra!

This is a study for the 1888 painting.

Danish bar interior

Ved frokosten. Kunstneren og hans hustru med forfatteren Otto Benzon. Skagen. Peder and Marie lunching with Otto Benzon, Skagen

Marie was the subject of a number of paintings while the marriage was going well. She also appeared as a member of the cast of social scenes, as can be seen here.

Photo of Peder and Marie Krøyer

I include this so that you can judge how well Krøyer was able to capture Marie.

Marie Krøyer - 1889

Marie Krøyer - 1890

Sommeraften ved Skagen - Marie in Skagen, summer evening

Monday, June 20, 2011

Albert Kahn: Versatile Architect

Perhaps I wrote too soon. I've always liked the work of architect Raymond Hood and made a modest case for him here, stating "I base my contention on Hood's ability to do outstanding work in several styles: traditional, Deco and modernist."

So what did I do a few weeks later than pick up a book I bought in Detroit a few years ago and thumb through it. What I saw was strong evidence that there was another guy who could (or maybe guys in his firm under his direction could) do what Hood was doing at a similar level of competence for a lot more structures. He was Albert Kahn (1869-1942). His Wikipedia entry that includes a list of his buildings is here.

One difference between the two architects is that modernists generally embraced Kahn more than Hood thanks to the industrial buildings he did during Detroit's boom days. They featured simplified shapes and little or no decoration, catnip to functionalist theorists circa 1925. His traditionally styled works ... well, they were conveniently set aside.

For what it's worth, Henry Ford had his anti-semitic moments, yet hired this rabbi's son to design his most important factories.

Here are some of Kahn's buildings.

Gallery

Dodge Brothers plant, Hamtramck - 1910

Angell Hall, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor - 1922

General Motors (Durant) Building, Detroit - 1922

Fisher Building - 1927

Albert Kahn House, Detroit - 1907

E. Chandler Walker House, Windsor, Ontario - 1905

Cranbrook (George Booth) House, Bloomfield Hills - 1907

Edsel Ford House, Grosse Pointe Shores - 1926

The Edsel Ford House, conceptually a cluster of Cotswold cottages, is open to the public and well worth the effort to get there. (It's in one of Detroit's poshest suburbs, so rent a car and enjoy checking the neighbor's digs en route.) Most of the rooms are decorated in late 1920s style. Exceptions are bedrooms used by Edsel's sons which were redecorated in a Moderne mode around 1940.

Friday, June 17, 2011

Art My Teachers Made

I'm years away from the art training scene, which means I'm seriously out of touch. Besides, I went to only one school, and conditions do vary from site to site.

Having proclaimed my near-total ignorance, I'll now wildly assert that the typical university-based art department probably has only a few instructors whose names and work are known much beyond the location of the nearest off-campus tavern.

I attended the University of Washington, overlapping Dale Chihuly and Chuck Close who somehow made good despite having experienced the sort of non-instruction I got. The best-known instructor of that general era was Jacob Lawrence, but he arrived after I'd graduated. The others had some local notoriety, but no real national reputations so far as I can tell.

Just for kicks, below are a few examples of their work that turned up on the Internet.

Gallery

Wendell Brazeau - Still Life

Boyer Gonzales, Jr. - abstract landscape

Gonzales was the Art School head and taught little. His father, Gonzales, Sr., was also an artist and probably better known than the son.

Ray Hill - Oregon Coast Near Cannon Beach

I wish I could have found a more characteristic example of Hill's work. He painted clean, somewhat abstracted work that reminded me of Lyonel Feininger's mildly Cubist paintings. I think Hill was either emeritus or nearly so when I was in art school, so I never had a class from him -- but would have liked to.

Alden Mason - Burpee Red Surprise - 1973

Spencer Moseley - Shore Birds - 1952

Valentine Welman - abstracted landscape

Welman had an especially varied career, winding up as a sculpttor. And he was the guy stuck teaching commercial art, so I spent a lot of time in his classroom.

As can be seen, they mostly painted in the modernist, abstract or semi-abstract vein. Most of them ranged in age from 30 to 60, which suggests that they trained when modernism was becoming accepted, but that their own training was more traditional than what they practiced. Aside from a Freshman design class where we used colored paper, scissors and paste to create works, I never experienced a class that featured abstraction. On the other hand, faculty were loath to offer technical instruction, likely in fear that such training would stifle our precious "creativity."

I need to mention that I didn't take classes from all the artists noted above, though all were teaching at that time. It has been so many years that I've forgotten what I took from whom in many cases.

Left out are two instructors whose classes I did attend but whose work I was unable to find on the Web. Another instructor I had, George Tsutukawa, is worth a post of his own, and I'll get to it at some point.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Useful Paintings

The title of this post, "Useful Paintings," is the name I gave to a directory on my main computer. That directory contains out-takes of images I've been accumulating from various Internet sources.

(The Internet becomes increasingly useful as it expands and servers gain enough storage room to hold images greater than a megabyte in size. When I started blogging at 2Blowhards, we tried to keep image size down to 50K, which forced me not to use certain images that I truly wanted to include.)

I currently have directories devoted to "Painters," "Illustrators" and "Modernist Painters" with sub-directors by artist's name. Each main directory contains a "miscellaneous" slot holding too few images by any artist to justify a devoted directory. As images accumulate, from time to time an artist will be promoted to his own sub-directory. I've been finding that I have less need for buying art books chosen mostly for their images (rather than for textual information; the Internet allows me to have a very good art reference collection at virtually no cost in space and coin).

That "Useful" directory contains images that provide me information regarding use of color, brush technique, and other artistic factors. Some are included simply because I like them and there's less need to dig around to locate them elsewhere.

You might notice that all the images shown below depict beautiful women; that's because I like paintings of beautiful women and that directory is almost entirely filled with images of paintings of them.

I'm thinking that, from time to time, I'll do similar posts showing other images from that directory. Hope you don't mind beautiful women.

Gallery

Étude du femme - John White Alexander - c.1890

Erubescent - Casey Baugh

Asidua del Moulin de la Galettte - Ramon Casas - 1891

My Daughter Dieudonnée - William Merritt Chase - c.1902

Deguisement - Virgilio Costantini

Monday, June 13, 2011

Stanhope Forbes at Low Tide

A painter whose work I'd like to see more of in person is Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) who was the anchor of an artists' colony not far from Land's End. I visited England last summer and tried to come up with a plan to include Cornwall in the itinerary. But with only six days to work with between my wife's Wimbledon experience and a jaunt to Paris, I couldn't pull it off. She wanted to see Stratford, Bath, Stonehenge and Brighton and I had set up a get-together with frequent commenter "dearieme" at the fringe of the lower Midlands. Maybe next time.

Forbes' brief Wikipedia entry is here and a bit more biographical information can be found here, here and here.

This BBC item says that the painting shown above, his "Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach" (1885), is one of the most important works in the Plymouth Museum. And it is a fine piece of work. I know this because I've seen it even though the closest I ever got to central Plymouth was the freeway interchange to the road coming down from Dartmoor. By some miracle it was in San Francisco a few years ago where I chanced upon it and was mightily impressed.

One thing that impressed me that a casual view might miss was Forbes' treatment of small, background figures. He defined faces, clothing and other "details" with a few well-chosen brush strokes using carefully selected colors. I wished I could be even half that good.

The original painting is fairly large, as is the image above if you click on it to enlarge. Even so, the image is much too small to view what I just mentioned. The only solution is to buy a large, good reproduction if you can't make it farther west than Oxford or Bath on your next trip to England.

Friday, June 10, 2011

New Objectivity as Echo

In the shattered aftermath of the Great War and the emergence of Modernism during the first 20 years of the 20th century, painters were faced with a What The Devil Do We Do Next situation. Various this's and that's popped up including a German movement called New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit).

It was rather ill-defined, as this Wikipedia entry indicates. There was the gross (pardon the pun) , crudely-drawn work of George Grosz. And then there was the calmer, less anger-fueled work of Christian Schad, who I'm likely to return to in future posts.

Schad fell into the distorted, cartoon-like New Objectivity practice, but not very far. What I find interesting is that his work sometimes resembles early paintings by untrained or poorly trained American painters. I doubt that he was aware of this American art, so what we have is simply a striking coincidence and not inspiration. Take a look:

Graf St. Genois - Christian Schad, 1927

Man Holding a Large Bible - Anni Phillips, c. 1826

Bettina - Christian Schad, 1942

Girl With Bird and Cage - Unknown artist, c. 1735-40

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Sundblom's Buttery Illustrations

Haddon Sundblom (1899-1976) is one of those illustrators whose work I greatly respect and almost, but don't quite, love.

His Wikipedia entry offers a too-short sketch of his career. At least it makes the point that a number of other competent illustrators worked at his studio and were influenced by him; this is one of his important claims to fame.

Leif Peng has dealt with Sundblom on his blog, and you might want to click on these links.

What maintains Sundblom's fame (among illustration buffs, anyway) is the work he did for Coca-Cola. He painted many illustrations of Coke-enjoying people for print, poster and billboard advertising. But the big thing was his Santa Claus series and, to a lesser extent, the "Frosty" character -- a smiling elfin creature always posed by a bottle or glass of the beverage.

Here are examples of Sundblom's work, with a slight emphasis on his earlier illustrations.

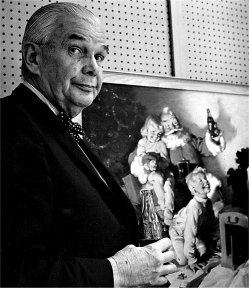

We might as well start with a Santa. From what I've read, Sunblom began to use himself as his model as he aged into the part.

Here's Sundblom when he was older and in synch with his Santas.

And, just for the record, here is a Coke ad, probably from the 1940s.

Now for some non-Coke illustrations, this being an ante-bellum Southern scene.

A 1920's illustration.

Also from the 20's.

Magazine cover art.

This is a later painting, probably done in the 1940s when he applied paints thicker and smoothly, a practice he was following by the mid-1930s.

Magazine work from 1933.

I respect Sundblom for his skill in portrayal and, especially, for his way of handling paint in a pleasing thick, buttery manner.

Yet something bothers me just enough that I can't place Sundblom with contemporaries such as Dean Cormwell, John La Gatta and Mead Schaeffer. Maybe it had to do with stereotyping or pigeonholing by clients and art directors. Perhaps it was Sundblom's preference. In any event, the result was that little of his work had drama or "bite" of any kind. To some degree this is like fellow Chicago illustrator Andrew Loomis whose style was somewhat similar and whose subjects were more pleasant than edgy or dramatic. This is not to say that I favor drama and edginess -- though a whiff of something like that either in subject matter or painting technique appeals to me for some reason.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)